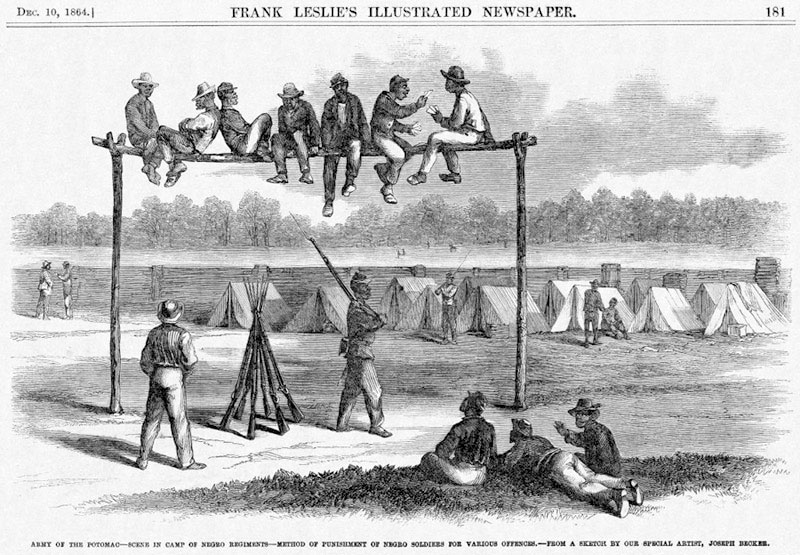

"Army of the Potomac—Scene in camp of Negro regiments—Method of punishment of Negro soldiers for various offences." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, December 10, 1864.

A recent post on The Huntington Library blog entitled “Captured in Translation” compares a Civil War photograph and news engraving to demonstrate the discrepancies between photographs and their adaptations into mass-produced formats in the era before photo-mechanical reproduction. The blog post by Steven Robles is a useful comment on the importance of attending to the strengths and weaknesses of archival visual evidence; it also raises a question about whether “translation” is the process we need to evaluate.

The photograph and engraving both show African-American soldiers being punished on a “wooden horse.” But the photograph, which is in The Huntington’s James E. Taylor collection of Civil War images, “captures just two soldiers straddling the suspended beam with stoic faces,” while the engraving published in the December 10, 1864 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (above), shows seven soldiers perched on the beam, “some playing cards while others nap.” The nonchalance and obstreperousness exhibited by the punished black soldiers in the engraving appear to support the illustration’s accompanying textual description, which condescendingly claimed that black troops required greater discipline than white soldiers because of their “obtuse sensibilities.” That bias prompted Steven Robles to be skeptical about the claim in the description that the “drawing is from life.” Without directly saying so, he suggests that the photograph was the actual source for the illustration. Thus, the comparison seems to offer an example of the limitations of the process of translation from photo to engraving imposed by the reproductive technology of the time, which “allowed for some creative adjustments on the part of the illustrators.”

But should we assume that the engraving was a translation of the photograph? The photo is in the collection of images by James E. Taylor, who was one of the more prolific of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper‘s special artists covering the war—and, therefore, one might be led to conjecture that Taylor was the artist who made the sketch upon which the engraving was based. But the drawing was the work of another Leslie‘s artist, Joseph Becker, who rendered it in October 1864 during the siege of Petersburg (it can be viewed in the excellent online Becker Collection). While Becker undoubtedly made biased “creative adjustments” in this sketch (as he did throughout his long career, notably when covering the bitter 1874-75 “Long Strike” in the anthracite coal region of eastern Pennsylvania)—and certainly sketch artists used photographs as references for drawing uniforms, equipment, locations, and other visual details—this sketch and its subsequent rendition as an engraving were not translations of another medium.

Moreover, the question of bias and/or distortion is not only germane to the artist-reporter sketch or subsequent published wood engraving: the photograph’s depiction of black soldiers’ punishment also requires further consideration regarding interpretation. The soldiers’ stoic faces may be less evidence of their actual attitudes toward or behavior when facing punishment than an indication of the limits of photographic technology. The slow exposure time and stillness required of photographed subjects may have imposed those unreadable expressions.