State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss

Several armed men in uniform on the campus of the University of Mississippi, October 1, 1962. The men were part of the law enforcement effort to restore and maintain order on the campus during the riots that occurred after the integration of the university by James Meredith in late September. The Confederate monument in question is at left. (Special Collections, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.)

One of the most vivid stories a professor told me in graduate school was about the guy whose job it is to repair Civil War monuments, in particular the ubiquitous “Standing Soldiers” that dot the courthouse squares of small towns around the United States. We were discussing Kirk Savage’s brilliant Standing Soldier, Kneeling Slave: Race, War and Monument in 19th Century America, which is required reading for anyone interested in public history, memory and the Civil War. The professor in question had recently visited the Ole Miss campus where, not surprisingly, a Confederate soldier stands atop a monument at the entrance to the campus. Walking around the campus at night, my professor came across the repairman patching holes in the marble base of the statue, where the inscription reads “In memory of the patriotism of the Confederate soldiers of Lafayette County, Mississippi/They gave their lives in a just and holy cause.”

The two men chatted about the work; there are a lot of Civil War monuments (in fact, in the late 19th century the monuments were mass produced and manufacturers asked towns to specify whether to write “USA” or “CSA” on the belt buckles of the statues) and most statues are now about a hundred years old: suffice it to say, repairing Civil War monuments is good line of work if you can get it. My professor remarked that it was odd that these particular repairs were being done at night, though. The repairman told him there was a good reason for that: he was actually repairing bullet holes that had damaged the monument during the riots that engulfed Oxford when James Meredith tried to integrate the campus in 1962. Either the memory of the riots themselves, or the anger that such traces of violence during the 1960s were now being erased, were contentious enough that he had been asked to work at night when few others were around.

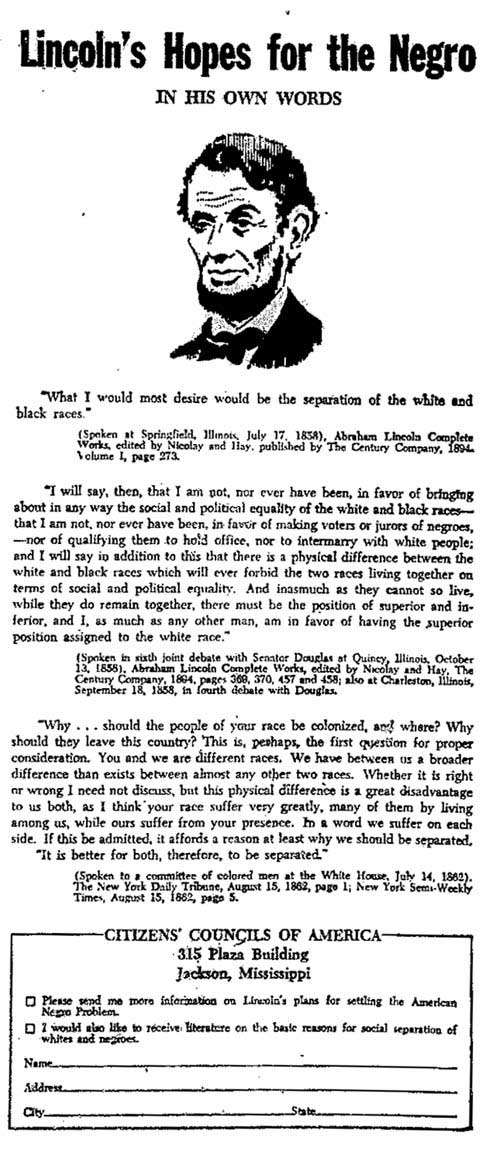

This newspaper ad was placed by the segregationist Citizens' Councils of America (based in Mississippi) in a Seattle newspaper in 1964 during open housing battles there.

The story caught my imagination: here we are, still repairing monuments that some would like to see relegated to the dustbin of history.* Moreover, some officials would rather preserve the Confederate monument and erase the more recent memory of the battle for integration and black civil rights. In this case, I think the bullet holes are important to preserve because the Confederate monument, I would argue, is no longer “complete” without the later evidence of the black freedom struggle. I wonder if there’s opportunity for some sort of intervention at the site even now, some sort of signage or artwork that could surface these questions about how we remember the past, and what it worth preserving.

This story is really just a long wind up for my pitch for the new American RadioWorks documentary State of Siege: Mississippi Whites and the Civil Rights Movement, which considers the uniquely strident efforts of white Mississippians to maintain segregation. (Maybe someone will make sure State of Siege winds up on Haley Barbour’s iPod to remind him that things weren’t as sunny as he remembered them.) Mississippi segregationists ardently defended segregation at home and around the country. I came across the add a left, placed in a 1964 Seattle newspaper, while researching open housing campaigns: clearly white Mississippians were looking for allies anywhere around the nation where they thought their message might resonate. Further, they made an explicit link between the Civil War era and the current battle over citizenship and rights.

Nearly always present at pro-segregation rallies was the Confederate battle flag, which helped to further conflate Civil War memory and the black freedom struggle. If you are interested in hearing more discussion about the contentious memory of the Civil War–and in particular, the persistent and insidious divide between how scholars and the general public understand the conflict–you are welcome to attend ASHP/CML’s upcoming FREE public panel “The Great Divide? Civil War Myths and Misinformation” on Tuesday, April 5 at 6pm at the CUNY Graduate Center.

*For more on what to do with Confederate monuments, I highly recommend Sanford Levinson’s Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies.

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- The Good Old Days of Uncomplicated Civil War Narratives - February 1st, 2011