Pigskins and Blue Eagles

September 1st–it’s officially football season now! That makes it high time I posted another blog entry on the social history that inspired the names of sports teams. Let’s take a look at the Philadelphia Eagles, shall we?

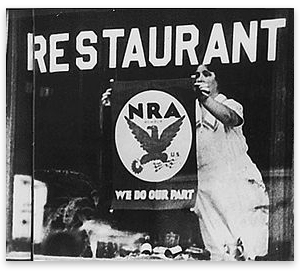

Might these lovely ladies--sporting the NRA's eagle logo--have been found on the sidelines of the Philadelphia Eagles' first home games?

N.F.L. owners may be big funders of conservatives today–one blogger joked the acronym might as well stand for “Not For Liberals”–but the first team owners of the Philadelphia Eagles had very different political allegiances when they named their team in 1933 after the eagle logo of the National Recovery Administration. Or perhaps they were hoping to tap into the popularity of the program and found that the ubiquitous blue eagle logo would give the team some free advertising. Then again, since it was the second attempt to establish a professional N.F.L. franchise in Philly, maybe the owners wanted a “New Deal” for Philadelphia football?

The blue eagle logo–which my grandmother remembers seeing in stores and during parades in her hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts–was displayed prominently in the windows of businesses that agreed to new codes for hour limits, minimum wage and production standards. The codes were negotiated among business leaders, labor leaders and Roosevelt administration bureaucrats, though most realized that without a strong union movement, there wouldn’t be sufficient oversight of industry to enforce them. Section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Act, which gave employees “the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing…free from interference, restraint, or coercion of employers”–became known as the Magna Carta of Labor. Gone were the days of yellow-dog contracts and forced membership in company-sponsored unions. Section 7a ushered in a a new era for labor, as millions of workers joined industrial unions. In some industries, particularly mining, which had great enforcement strategies in place, workers were able to leverage their new power into even greater concessions on wages, hours, and issues like child labor. In other industries, especially where unions were headed by radicals, African Americans or Mexican Americans, employers ignored N.R.A standards. The N.R.A. had only limited successes, then, before it was declared unconstitutional in 1935. Even so, the strengthened labor movement that grew out of Section 7a led to the wave of strikes in 1934, the big Democratic majorities elected in 1936, and the leftward turn of the Second New Deal–including the most radical legislation of the period, the Wagner Act.

The blue eagle logo–which my grandmother remembers seeing in stores and during parades in her hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts–was displayed prominently in the windows of businesses that agreed to new codes for hour limits, minimum wage and production standards. The codes were negotiated among business leaders, labor leaders and Roosevelt administration bureaucrats, though most realized that without a strong union movement, there wouldn’t be sufficient oversight of industry to enforce them. Section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Act, which gave employees “the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing…free from interference, restraint, or coercion of employers”–became known as the Magna Carta of Labor. Gone were the days of yellow-dog contracts and forced membership in company-sponsored unions. Section 7a ushered in a a new era for labor, as millions of workers joined industrial unions. In some industries, particularly mining, which had great enforcement strategies in place, workers were able to leverage their new power into even greater concessions on wages, hours, and issues like child labor. In other industries, especially where unions were headed by radicals, African Americans or Mexican Americans, employers ignored N.R.A standards. The N.R.A. had only limited successes, then, before it was declared unconstitutional in 1935. Even so, the strengthened labor movement that grew out of Section 7a led to the wave of strikes in 1934, the big Democratic majorities elected in 1936, and the leftward turn of the Second New Deal–including the most radical legislation of the period, the Wagner Act.

The National Recovery Administration, and the Public Works Administration that fell under its authority, had a big impact on Pennsylvania, though. The Great Depression had hit the state’s manufacturing base hard: 270,000 workers lost their jobs between 1927 and 1933 as 5,000 manufacturing firms closed. Cities and rural areas both suffered; one report had rural Fayette County’s unemployment rate at 37%. In 1931, Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot–a Republican!–declared “the only power strong enough, and able to act in time, to meet the new problem of the coming winter is the Government of the United States.” Despite these problems, however, Pennsylvania was one of only six states to vote for Hoover in 1932. Even so, between July 1933 and March 1939, the Public Works Administration spent over $6 billion on more than 34,000 construction projects; the Civilian Conservation Corps employed 200,000 men in Pennsylvania alone. Anyone who has ever driven across the state will also be thankful that the P.W.A.-built Pennsylvania Turnpike provides a welcome alternative to drab I-80. New Deal programs were popular enough that in 1936 Democrats were finally elected to majorities in the state house and to the governorship for the first time since the 1890s. Still, throughout the 1930s, the New Deal coalition barely held in the state, as conservatives exploited tensions between ethnic white and black workers, especially in Philadelphia. (See here for even more about the New Deal in Pennsylvania.)

Maybe Eagles players, like all N.F.L. union members, should pay homage to the legacy of their namesake during the next round of negotiations with owners? In any case, knowing this history will add a fun dimension to the first game of the Eagles season, when they face off on opening Sunday against the other N.F.L. team with a name that calls to mind labor history and workers, the Green Bay Packers!

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss - March 25th, 2011