The Perfect Summer Song, with a Dash of Social History

There may only be a few more weeks of summer left, but it’s still hot and sticky in New York City. Â So there’s time enough to blog about my favorite summer song and a bit of the social history behind it. Â Just try and resist the many charms of Joe Cuba’s 1966 boogaloo hit “Bang, Bang”:

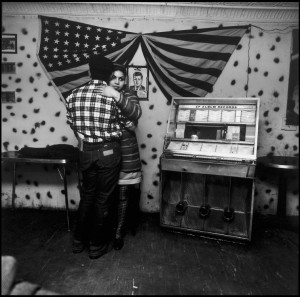

Bruce Davidson, COUPLE BY JUKEBOX IN SOCIAL CLUB, 1966, from the series East 100th Street

Boogaloo (bugalú in Spanish) emerged out of the close contact between Puerto Ricans and African Americans in Harlem and East Harlem in the mid 1960s.  At the time, African-American youth–the children and grandchildren of the first and second Great Migrations– were playing in the street, attending school, and partying in rec centers and clubs with the large generation of Puerto Rican kids then coming of age in New York.  Joe Cuba (born in New York to Puerto Rican immigrants) and his band created a song that would appeal to their mixed black and Puerto Rican audiences: you’ll hear distinctively Latino percussion and rhythms laid over a characteristically African-American backbeat.  The band members shout out R&B phrases like “Sock it to me” and Spanish phrases one after another.  Then they call out soul foods–“cornbread, hog maw, and chitterlings”–and suggest a few Puerto Rican versions of the same foods: cuchifrito and lechón.  The song is downright giddy, with stops and starts, showcasing musicians like Cheo Feliciano improvising lyrics and Jimmy Sabater playing the life out of his timbales.  It’s easy to picture a group of kids crowded around a record player in some tenement basement in East Harlem; that’s the intended vibe, anyway, of the children singing along with the chorus in the song.  “The overall effect” as sociologist Juan Flores describes it,

is one of collective celebration, gleeful partying where boundaries are not set so much by national and ethnic affiliation, or even language or formalized dance movements, but by participation in that special moment of inclusive ceremony… [The] defining theme and musical feautre of boogaloo is precisely this intercultural togetherness, the solidarity engendered by living and loving in unison beyond obvious differences.

Juan Flores, From Bomba to Hip-Hop: Puerto Rican Culture and Latino Identity, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 82.

The year before “Bang, Bang,” the Joe Cuba Sextet had scored another hit referencing the African American experience: the signature line of “El Pito (I’ll Never Go Back to Georgia)” was borrowed from Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca.”  “I’ll never go back to Georgia” captures the voice of a Southern black migrant vowing never to return to Jim Crow.  Gillespie first wrote the lyric in the 1940s, and Jimmy Sabater was struck both by the sentiment and the way the cadence of the line perfectly fit a clave rhythm.  And in 1965, when the song came out, the political timing was just right to make “El Pito” a rare crossover hit for Latin and black audiences.  In the liner notes for a recent re-issue of the album, pianist and arranger Nick Jiménez relates that the Georgia legislature even protested the song.

Within a few years, Nuyoricans would turn away from explicitly referencing black music and culture, embracing salsa as “Our Latin Thing.” Â Around the same time, hip-hop, pioneered by both African-American and Latino musicians in the South Bronx, would end up being marketed and thus largely thought of as black music. Â Boogaloo, though, was a purposeful sharing of cultural and social experience in song in the mid-1960s. Â It also just happens to be the perfect playlist for mid-August in New York City.

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss - March 25th, 2011