Freedom to Marry–Then and Now

The 14th Amendment has been everywhere in the news these days, what with calls to repeal the provision that provides citizenship to anyone born in the United States, to its application of “equal protection under the law” in Perry vs. Schwarzenegger in declaring California’s ban on gay marriage unconstitutional.

This part of Judge Vaughn Walker’s ruling in California really caught my eye, though:

The states have always required the parties to give their free consent to a marriage. Â Because slaves were considered property to others at the time, they lacked the legal capacity to consent and thus unable to marry. Â After emancipation, former slaves viewed their ability to marry as one of the most important new rights they had gained.

As Judge Walker notes, freedpeople immediately began to reunite their families and legally register their marriages following emancipation. Â The urge to form families was powerful: even before the war was over, former slaves appeared before Union army officials demanding legal marriage:

Weddings, just now, are very popular and abundant among the colored people. Â I have married during the month twenty-five couples, mostly those who have families, and have been living together for years.

–Union Army chaplain, quoted in Eric Foner and Joshua Brown, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 83.

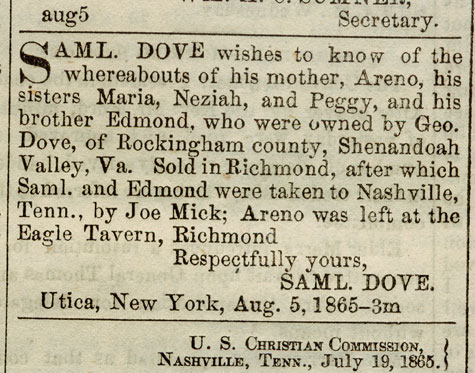

When the war finally ended, freedpeople traveled great distances to find their families and placed ads in newspapers to find relatives long separated by the auction block:

This meeting again of mother and daughters, after years of separation and many [hardships], was an occasion of the profoundest [deepest] joy, although all were almost wholly [without] the necessities of life. Â This first evening we spent together can never be forgotten. Â I can see the old woman now, with bowed form and gray locks, as she gave thanks in joyful tones yet reverent manner, for such a wonderful blessing.

–Louis Hughes, whose wife found her mother and sister in Cincinnati, Ohio after the Civil War

The Colored Tennessean, August 12, 1865, courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society

Because marriages between slaves before emancipation had no legal standing, many couples rushed to have their marriages officially registered and made solemn during Reconstruction.

After while I taken a notion to marry and massa and missy marries us same as all the niggers. They stands inside the house with a broom held crosswise of the door and we stands outside. Missy puts a li’l wreath on my head they kept there and we steps over the broom into the house. Now, that’s all they was to the marryin’. After freedom I gits married and has it put in the book by a preacher.

–Mary Reynolds, who was a slave in Louisiana, in an interview for the W.P.A. Slave Narratives Project

Here Anna Marie Coffee recounts getting a license in 1868, the same year the 14th Amendment was adopted.

I went to church in Monticello [Kentucky], and there I finally married Henry Coffee. Â Henry, he’d been in the war, and belonged to the 6th Kentucky Calvary. Â Us was the third colored couple to get [a] marriage license in 1868… Â Then [we] moved to London [Kentucky], and Henry farmed and done first one thing and another to make a living. Â We bought a nice little place and lived real nice, and worked in the church.

–Anna Marie Coffee, interview for the Works Progress Administration Ex-Slaves Narratives project

Alfred R. Waud, Marriage of a Colored Soldier at Vicksburg by Chaplain Warren of the Freedmen's Bureau, drawing, c. June 1866, The Historic New Orleans Collection, http://www.hnoc.org.

The above sketch shows a chaplain marrying an African-American couple in the offices of the Vicksburg, Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau. The sketch was the basis for a news illustration published in Harper’s Weekly.  The significance–and novelty–of the marriage of two former slaves was newsworthy in 1865.  Eventually the Freedmen’s Bureau became strong advocates of legalized marriages and helped former slaves find their families.  But Bureau agents were only responding to the demands of freedpeople, as historian Eric Foner recounts:

Two years after the end of the Civil War, freedman Hawkins Wilson sought the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau in locating family members he had not seen since being sold away from Virginia twenty-four years earlier. Â “I am anxious to learn about my sisters,” Wilson wrote, “from whom I have been separated for many years.” Â He went on to list the names of “my own dearest relatives”: his sisters, brothers-in-law, nephews and nieces, and uncles, along with their owners at the time of his sale. Â He also enclosed recent experiences. Â Since emancipation, Hawkins related, he had learned to read and write, secured a job in a furniture workshop, became a sexton in the Methodist Episcopal Church in Galveston, Texas, and played a leading part in mass meetings at which former slaves demanded the rights of citizenship. Â He had also married ” a very intelligent and lady-like woman.” Â “Thank God,” Wilson added, “that now we are not sold and torn away from each other as we used to be.”

-Foner and Brown, Forever Free, 84.

Wilson’s story reminds us that families existed, whether the law and society recognized them or not, under slavery. Â The right to solemnize and legalize these relationships was paramount in the aftermath of slavery; through their actions, freedpeople demonstrated that full citizenship meant the right to marry and form families. Â These historical reflections seem to be strikingly relevant in today’s debates about gay marriage.

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss - March 25th, 2011