A Little Perspective on the Ills of the Tobacco Industry

Today’s story in the New York Times that Phillip Morris, the tobacco-and-other-things-that-aren’t-good-for-you company, “benefits” from child labor in Kazakhstan should surprise no one familiar with multinational corporations or the history of the tobacco industry. Â The article seems to dance around the issue, using a verb like “benefits” from, rather than “employs” or “uses”, child labor. Â It seems that Phillip Morris purchases tobacco from suppliers who use migrant farmers–both adults and their children–who earn a few hundred dollars a year for their labor. Â (The peculiarities of this supply chain, the company (and the editor who gave the article its title) tells us, absolves them to some degree of responsibility for the situation.)

The story calls to mind the work of Progressive reformers to document child labor, especially in the tobacco industry, around the turn of the century. Â Lewis Hines’ photos for the National Child Labor Committee are particularly famous:

"10 year old leaf boy and three "stringers" 10, 12, and 13 years old. Tobacco shed of American Sumatra Tobacco Co. In these two sheds were 41 girls and boys from 10 to 15 years, and only 24 girls and women of 16 years and up. The leaf-boys get $1.50 a day and some of the stringers of 10 and 12 make $1.20 a day, according to the Supt. Location: South Windsor, Connecticut"

![Spiking tobacco on Lowe farm. Roland 13 and Bush 14 years old will go to Pretty Run School in a week or two, when tobacco is all in. It is a school day and school began 2 months ago. Boys say they have been in school some this year. Location: Clark County--Winchester [vicinity], Kentucky](http://ashp.cuny.edu/nowandthen/wp-content/uploads/00531r-300x211.jpg)

"Spiking tobacco on Lowe farm. Roland 13 and Bush 14 years old will go to Pretty Run School in a week or two, when tobacco is all in. It is a school day and school began 2 months ago. Boys say they have been in school some this year. Location: Clark County--Winchester, Kentucky"

"Group of girl workers at the gate of the American Tobacco Co. Young girls obviously under 14 years of age, who work about 10 hours every day except Saturday. Wilmington, Del., 05/1910"

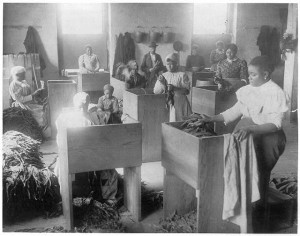

However, this earlier photograph (circa 1899) shows African-American women in Virginia “assorting tobacco.” Â There is clearly a young child sitting on the floor doing the same:

(Another photograph, from the same company, features African-American men working on a different part of the production of tobacco, showing how different steps in the factory production process were heavily gendered, though we know from many other photographs that the work of growing and harvesting toboacco on the farm was shared equally by men and women.)

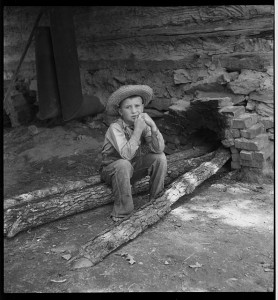

Farm Security Administration photographs from the 1930s and 1940s show that, though New Deal reforms managed to stabilize tobacco prices, children were still an important part of the labor force in the industry:

"Ten year old son of tobacco sharecropper can do a "hand's work" at tobacco harvest time. Granville County, North Carolina"

(Same Boy as Earlier Photograph) "Ten year old son of tobacco tenant tends the fire which is curing the tobacco in the barn. Granville County, North Carolina"

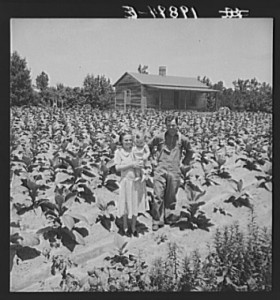

What may be less obvious from the photographs is that the children were not only victims because they were poorly paid to break their backs growing highly addictive crops. Â No, as if that weren’t enough, tobacco production produced epidemiological rates of pellagra in the South from the 1890s to the 1950s. Â This photograph, also from the Library of Congress, demonstrates why:

"Sharecropper with wife and child in their tobacco field. Note that the tobacco grows up to the front porch. Near Chapel Hill, North Carolina"

Pellagra is caused by a vitamin deficiency that comes from subsisting almost entirely on a corn-based diet. Â It started showing up in peasant societies throughout Europe shortly after corn was introduced from the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Â Then, around the turn of the century in the United States, and especially the South, pellagra became rampant. Â It appeared to researchers and public health workers to be another unfortunate example of a “poor people’s disease”; the source of the problem eluded them.

What accounted for this sudden spike in pellagra among the poor?  The photograph above shows (and the original caption hints at) the cause: the poor stopped planting gardens full of nutritious vegetables.  The southern diet had always been corn-based, but changes in farming and, in the case of sharecroppers, tenancy policies during the 1890s, meant that the poor no longer supplemented their diet with other vegetables.  They either felt pressure, from falling prices for tobacco and cotton, to grow crops up to their doorsteps, or their landlords demanded that all available land be turned over to commodity cultivation.  Thus Southern farmers stopped growing any food for themselves and bought all their food–now dried, canned, or packaged–at plantation stores.  The story was similar for  textile workers and coalminers, who rarely had space for gardens in company towns and bought their overpriced and under-nourishing food at company stores.

Unfortunately, both the story of pellagra and the long history of child labor in America’s tobacco industry mean there’s nothing surprising about Phillip Morris’s current use of migrant child labor in Kazakhstan.

(An excellent synthesis of the pellagra crisis can be found in Jack Temple Kirby’s Mockingbird Song: Ecological Landscapes of the South [UNC Press, 2006].)

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss - March 25th, 2011