Douglass goes public

After an inordinate delay, Frederick Douglass Circle opened yesterday at the northwest corner of Central Park and 110th Street in New York City. I assume there will be some sort of official unveiling ceremony, but as of this moment news of this long-awaited event has been muted. Indeed, a captioned photograph appeared in this morning’s print edition of the New York Times, but not on its website—and, as far as I can tell, no notice appeared in the city’s other daily newspapers (although I admit I didn’t check the subway hand-outs).

After an inordinate delay, Frederick Douglass Circle opened yesterday at the northwest corner of Central Park and 110th Street in New York City. I assume there will be some sort of official unveiling ceremony, but as of this moment news of this long-awaited event has been muted. Indeed, a captioned photograph appeared in this morning’s print edition of the New York Times, but not on its website—and, as far as I can tell, no notice appeared in the city’s other daily newspapers (although I admit I didn’t check the subway hand-outs).

Aside from the delay in the completion of the plaza (six years), some controversy swirled around the circle’s design when it was announced that the eight-foot statue of Douglass would stand on top of a granite quilt, composed of an array of squares each of which displayed a symbol recalling the secret code sewn into quilts that helped guide fugitive slaves northward along the Underground Railroad. That particular aspect of the design by Algernon Miller neither reflected Douglass’s own escape to freedom nor, despite the current popularity of such accounts, was it based on fact. The online photos of the opened plaza that I was able to locate seem to indicate that the quilt plan was abandoned.

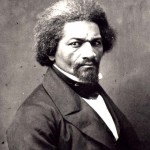

But what about the representation of Frederick Douglass, himself? Perhaps no nineteenth-century figure was as self-aware about the impact of his public visual image as he was, so this matter bears some consideration. Indeed, Douglass objected to a rather pleasant portrait of himself published in A Tribute for the Negro, an 1849 compendium of African and African-American achievement compiled by the Quaker abolitionist Wilson Armistead, complaining that the engraving had “a much more kindly and amiable expression, than is generally thought to characterize the face of a fugitive slave.â€Â Confronted by such uninspired portraits, not to mention the racist derision and viciousness that characterized antebellum U.S. visual culture, Douglass questioned if any white artist could accurately capture an African-American countenance (you can see the 1849 portrait and read Douglass’s comments on ASHP’s Picturing History website). As a consequence, Douglass preferred the new medium of photography, which gave him greater control over the way he wished to be viewed, forcefully staring back at the viewer.

Sculptor Gabriel Koren seems to have based the face of his Douglass (left) on a photograph taken around 1866 (right). The statue certainly conveys a gravitas that Douglass might have liked. I’ll leave it to others to evaluate the statue’s accuracy—measuring that against the demands of monumentality—or to gauge if the statue’s physical proportions work. For me, though, this Douglass’s left hand seems uncharacteristic of the man; it’s inert, oddly just, well, there: more appropriate to a mannequin than the legendary abolitionist. Bespeaking his greatness as an orator, his right hand appropriately rests on a dais. As a counterpoint, though, to capture Douglass’s passion, his relentless pursuit of freedom and equality, that left hand: shouldn’t it have been balled into a mighty fist?

Last 5 posts by Josh Brown

- The Civil War Draft Riots at 150 – A Public Event - June 17th, 2013

- Alfred F. Young - November 7th, 2012