The Long Civil Rights Movement

Sit-in at Woolworth lunch counter in Jackson, Mississippi, May 28, 1963

Fifty years ago today, four African-American college students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University walked into the Woolworth’s department store in downtown Greensboro, sat at the lunch counter, and asked to be served. It was a powerful new milestone in the black freedom struggle, another signpost along a road littered with them, that pointed toward the dismantling of the legal basis for racial segregation in the U.S. The sit-in movement spread rapidly across the South, and during the winter and spring of 1960 at least 70,000 people, most of them African Americans, participated in sit-ins in more than one hundred cities.

Media accounts, and many histories, attribute the speed with which the lunch counter sit-ins caught on to the moral authority of the calm, well-dressed, polite students and the power of the mass media that spread their image far and wide, shocking the nation and the world. True enough. But there is a compelling case to be made that the sit-ins also spread like wildfire because the embers of the tactic had already been burning among black college students for nearly two decades.

According to a 1944 article in The Crisis by activist and attorney Pauli Murray, starting in the winter of 1943, students at Howard University staged their own sit-ins. It began with a handful of students acting independently. Three young women who, when finally served the hot chocolates they had ordered at a segregated lunch counter, refused to pay the 25 cents they were charged for drinks that ordinarily cost a dime, and were hauled off to prison as a result. Ruth Powell, who would sit for hours, unserved, at local lunch counters, staring at the waitresses who denied her service just to unnerve the restaurant’s management. And then there was William Raines, who urged whoever would listen to apply the logic of the “don’t buy where you can’t work” boycotts of the 1930s to lunch counters: “Let’s go downtown some lunch hour when they’re crowded. They’re open to the public. We’ll take a seat on a lunch stool, and if they don’t serve us, we’ll just sit there and read our books. They lose trade while that seat is out of circulation. If enough people occupy seats they’ll lose so much trade they’ll start thinking.”

Such scattered impulses coalesced into an organized campus movement, a Civil Rights Committee with subcommittees for publicity, legislative action, correspondence, finance, and direct action. The direct action subcommittee quickly identified stores and restaurants near the university that catered to whites only and selected their first target: the Little Palace Cafeteria. Murray describes what happened next:

The direct action sub-committee spent a week studying the disorderly conduct and picketing laws of D.C. They spent hours threshing out the pros and cons of public conduct, anticipating and preparing for the reactions of the white public, the Negro public, white customers and the management. They pledged themselves to exemplary behavior  no matter what the provocation. And one rainy Saturday afternoon in April, they started out. In groups of four, with one student acting as an ‘observer’ on the outside, they approached the cafe. Three went inside and requested service. Upon refusal they took their seats and pulled out magazines, books of poetry, or pencils and pads. They sat quietly. Neither the manager’s panicky efforts to dismiss them nor the presence of a half dozen policemen outside could dislodge them.

More groups of students entered the cafeteria at five minute intervals until the management closed it forty-five minutes later. The students responded by picketing on the sidewalk outside, carrying signs asking “We die together–Why Can’t We Eat Together?” After two days of pickets, the Little Palace Cafeteria changed its policy.

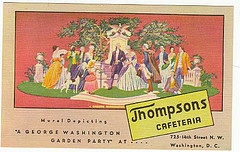

A year later, Howard students staged a similar protest at a Thompson’s cafeteria in downtown Washington, initially with similar results: “When 55 of them, including 6 Negro members of the Armed Forces, had taken seats at the tables, and the Thompson’s trade had dropped 50 percent in four hours, the management, after frantic calls to its main office in Chicago, was ordered to serve them.” Before the students could negotiate with Thompson’s management, however, nervous university administrators—knowing the havoc an irate congressman could wreak upon their funding—intervened and requested the students to “cease all activities designed to accomplish social reform affecting institutions other than Howard University itself.”

A year later, Howard students staged a similar protest at a Thompson’s cafeteria in downtown Washington, initially with similar results: “When 55 of them, including 6 Negro members of the Armed Forces, had taken seats at the tables, and the Thompson’s trade had dropped 50 percent in four hours, the management, after frantic calls to its main office in Chicago, was ordered to serve them.” Before the students could negotiate with Thompson’s management, however, nervous university administrators—knowing the havoc an irate congressman could wreak upon their funding—intervened and requested the students to “cease all activities designed to accomplish social reform affecting institutions other than Howard University itself.”

What the Howard University students began, their elders in Washington’s African-American community continued. In 1950, local activists formed the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of the D. C. Anti-Discrimination Laws (CCEAD), with Mary Church Terrell as chairperson. Even though the city did not have official segregation laws on the books, it took concerted pressure on local businesses to provide equal access to customers of all races. Where direct action failed, a lawsuit (District of Columbia v. John Thompson) against the Thompson’s cafeteria finally succeeded, in 1953. (For more on the CCEAD, see Beverly W. Jones, “Before Montgomery and Greensboro: The Desegregation Movement in the District of Columbia, 1950-1953,” Phylon, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2nd Qtr., 1982), pp. 144-154.)

Last 5 posts by Ellen Noonan

- Five Years - October 11th, 2012

- Patriotic Celebrations - July 4th, 2012