Segregation, in deed

In a story that could be played out in cities and suburbs across the country, for those who care to look, homeowners in the Charlotte, North Carolina neighborhood of Myers Park are discovering that the deeds to their properties contain what are known as “restrictive covenants,†language specifying to whom the property can be sold and how it can be used. Such restrictive covenants often included provisions used to discriminate against all manner of racial and ethnic groups, most commonly African Americans but also Asians, Latinos, and Jews. Legally unenforceable for more than six decades, they have generally faded into the municipal woodwork, seen only by recording clerks and real estate lawyers and rarely by property owners themselves. That changed in Myers Park when the neighborhood homeowners’ association posted a sample deed on its website, intending to remind residents of deeded restrictions on aesthetic concerns, such as fences, but instead drawing a complaint by the local NAACP and an investigation by the city.

Racially restrictive covenants came into being as a private method of maintaining racial separation after the U.S. Supreme Court declared local residential segregation ordinances illegal in 1917 (Buchanan v. Warley). In 1926, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of such private agreements in its ruling on Corrigan v. Buckley, which stood until 1948, when the court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that while individuals could enter into such contracts, courts could not enforce them. That left thirty years worth of legalized racial discrimination that facilitated the discriminatory allocation of public resources and hampered the accumulation of wealth among non-whites.

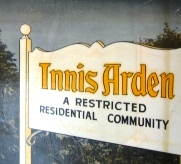

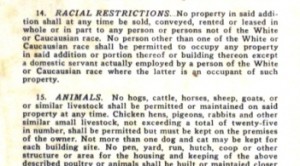

In an interesting and highly teachable project on this subject, the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project at the University of Washington has put together a set of online resources titled Segregated Seattle. Along with explanations of how racially restrictive covenants worked and maps showing residential segregation between 1920 and 2000, they have assembled a database of examples of restrictive covenants from King County dating from the 1920s into the 1940s. These examples could be powerful teaching tools, both in their specificity—the lists of every possible race excluded from ownership and residency, the exceptions for resident domestic servants of those restricted races—and in the boilerplate legal-ese that signals their ordinary place in the era’s real estate transactions. And of course, the northwestern location reminds us all that legalized racial discrimination was never merely a southern story.

Last 5 posts by Ellen Noonan

- Five Years - October 11th, 2012

- Patriotic Celebrations - July 4th, 2012