A Portrait from a Suffering Republic

This week ASHP/CML staff discussed Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War as part of our semi-regular staff reading series. Generally, reviews were mixed in our crowd, many of us feeling that too often Faust, in equalizing the mourning on both sides of the conflict, seemed decidedly apolitical about the causes for which they fought. (For those who have read the book, Eric Foner’s review is required reading.) While there were some parts of the books that really worked, such as the description of setting up national cemeteries in the war’s wake, there were other parts that did not, like Faust’s reliance on usual suspects Walt Whitman and Ambrose Bierce to talk about how the effect of the war’s destruction could be see in literature.

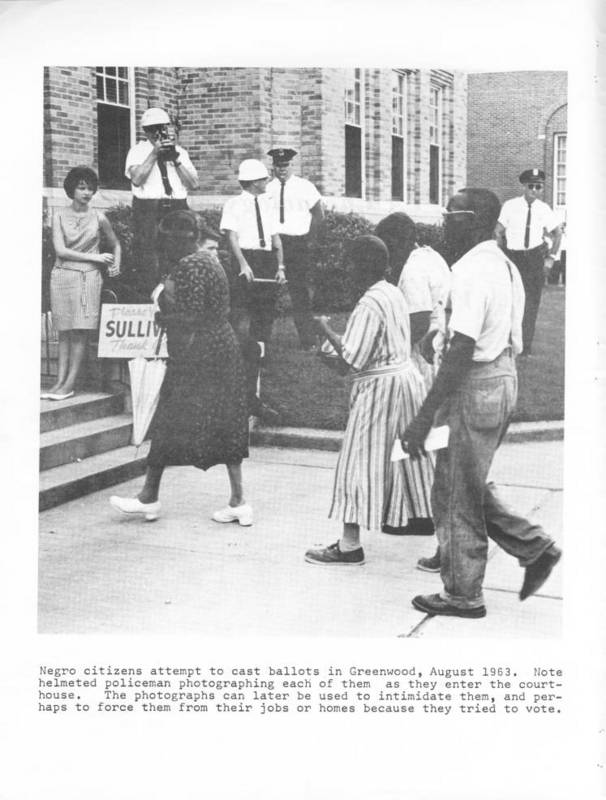

We all were frustrated that the book’s many images were used merely as illustrations, without context or comment on any. The simplistic and unexamined use of images among historians is exactly the problem that ASHP’s PUSH project hopes to rectify. In This Republic of Suffering, at the very least it seemed like a missed opportunity, and, given what we know about the importance of photography in the Civil War, at times it seemed a like a major oversight. I was reminded of this thread of conversation while looking through the images in the Library of Congress’s Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Portraits, recently announced in the Internet Scout Report. There I came across the portrait below, entitled [Unidentified girl in mourning dress holding framed photograph of her father as a cavalryman with sword and Hardee hat].

What a rich source to accompany Faust’s chapter “Realizing,” which looks at middle-class mourning customs and the “work” performed by civilians to come to terms with individual losses and the scope of death and misery caused by the war. For me the photograph is interesting because it is so similar to soldiers’ portraits, like the one she holds of the man who is presumably her father. The effect of the portrait’s similarity is heightened when one comes across it in a series of Civil War soldiers’ portraits, as I did on the Library of Congress’s website. One wonders who commissioned the photograph, who took it, who looked at it, and what each person thought of as they gazed upon the scene of grief and mourning. Was it part of a larger fad for taking pictures of wives and children in mourning, holding their loved ones’ portraits? Was this an image that one displayed on a mantle or held close to one’s heart? At what point did it become separated from the family whose grief it memorializes?

Good thing we are tackling Civil War photography as one of our subjects in the upcoming series Still Hazy After All These Years! For those of you in the New York area, mark your calendars now for February 3, April 5, and November 3. At the final date, we’ll be talking about photography with Anthony Lee, Mary Niall Mitchell, Martha A. Sandweiss and Deborah Willis.

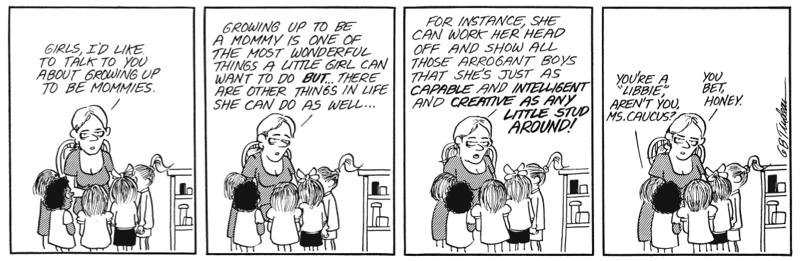

In honor of the comic strip Doonesbury’s 40th anniversary (the first strip was published in the Yale Daily News on October 26, 1970),

In honor of the comic strip Doonesbury’s 40th anniversary (the first strip was published in the Yale Daily News on October 26, 1970),  While I follow the strip only sporadically now, I have a very large soft spot for Doonesbury. When I was about 11 or so, I discovered my older brother’s soft-cover compilations and devoured them. Watergate and the end of the Vietnam war, which had existed on the fringes of my childhood consciousness, came into focus for me, along with Trudeau’s playful take on feminism and the counterculture. (My brother, or perhaps one of his friends, had starred all of the strips that dealt with Mark Slackmeyer’s fights with his father over the length of his hair, an argument I had heard plenty of times between my brother and my father. This is hilarious in retrospect, since my brother has been, as a teenager and ever since, the polar opposite of a countercultural figure. My vigilant father thought that any male head with hair longer than a crewcut was suspect.)

While I follow the strip only sporadically now, I have a very large soft spot for Doonesbury. When I was about 11 or so, I discovered my older brother’s soft-cover compilations and devoured them. Watergate and the end of the Vietnam war, which had existed on the fringes of my childhood consciousness, came into focus for me, along with Trudeau’s playful take on feminism and the counterculture. (My brother, or perhaps one of his friends, had starred all of the strips that dealt with Mark Slackmeyer’s fights with his father over the length of his hair, an argument I had heard plenty of times between my brother and my father. This is hilarious in retrospect, since my brother has been, as a teenager and ever since, the polar opposite of a countercultural figure. My vigilant father thought that any male head with hair longer than a crewcut was suspect.) In recent  years, Trudeau’s coverage of the war in Iraq has been particularly fine, depicting the humanity of ordinary soldiers with nuance and humor, and all without sacrificing its political edge. Doonesbury has also followed its soldier characters home from the battlefront, too, with long-playing stories of how they attempt to recover their physical and mental health. Sounds more bleak than funny? It’s not. That’s Trudeau’s gift, which has in many ways only improved with age.

In recent  years, Trudeau’s coverage of the war in Iraq has been particularly fine, depicting the humanity of ordinary soldiers with nuance and humor, and all without sacrificing its political edge. Doonesbury has also followed its soldier characters home from the battlefront, too, with long-playing stories of how they attempt to recover their physical and mental health. Sounds more bleak than funny? It’s not. That’s Trudeau’s gift, which has in many ways only improved with age.