A Primer on Working Class Sandwiches

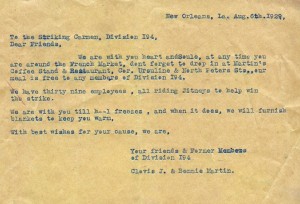

Though I’m partial to that other great New Orleans sandwich, the muffeletta, I couldn’t resist sharing this delightful story about the “lefty” origins of New Orleans’ iconic po’ boy sandwich. Â It seems that the Crescent City classic–crusty white bread encasing roast beef, shrimp, oysters and any other number of other hearty sauces or fillings–was created by two restauranteurs in solidarity with striking streetcar conductors in 1929. Â “We are with you till h–l freezes,” Clovis and Bennie Martin declared, and their support included offering free sandwiches and encouraging their employees to avoid the streetcars for the duration of the strike. Â They also cheekily offered blankets to keep the workers warm when hell finally did freeze over, if the strike should last so long.

The working-class origins of the po’ boy are all there: of course there’s the name that originally described the folks who ate them, as well as the common use of gravy and other sauces that provided cheap and filling calories for working people. Â The po’ boy story reminds me of another working people’s food I became familiar with when I lived in Rhode Island during graduate school: the chow mein sandwich. Â This southern New England “delicacy” is a combination of chow mein noodles and veggies and gravy dished over a piece of spongy white bread. Â Like other types of Chinese food, the chow mein sandwich was popular with the working classes because it was cheap and filling; eating out in Chinese restaurants also contributed to a growing “American” identity among disparate European immigrants, for whom the food was unlike anything familiar they prepared in their homes. Â The chow mein sandwich could easily be made “meatless” too, which contributed to its popularity with the mostly Catholic mill workers of places like Providence, Pawtucket, Central Falls (RI) and Fall River (MA). Â Though you’ll be hard-pressed to find chow mein on the menu in most Chinese restaurants today, if you ask around in the right places in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, folks will happily dish up this classic working class food.

Now, to bring it all home: the great popularizer of New Orleans cuisine, Emeril Lagasse, is a native of Fall River, Massachusetts (that accent is a dead give away, and his name is of French Canadian, not New Orleans Cajun, origin). Â Like any good local boy would, Emeril has a recipe for the chow mein sandwich. Â And, from his adopted home city, he’s got one for the po’ boy, too.

Learn more about doing your part (i.e., eating) to preserve the sandwich and its story at the site of the New Oreleans Po’ Boy Preservation Festival.

Last 5 posts by Leah Nahmias

- Teaching "What This Cruel War Was Over" - March 28th, 2011

- State of Siege and Public Memory at Ole Miss - March 25th, 2011