The Conspirator and the fate of historical print and visual culture

Robert Redford’s film The Conspirator has received many justifiably negative reviews (see the particularly astute comments of A. O. Scott in the New York Times). I would like to add one more criticism of the film’s overall inaccuracies, omissions, misrepresentations, and anachronisms (not to mention clichés, thin characterizations, poor staging, and tepid performances).

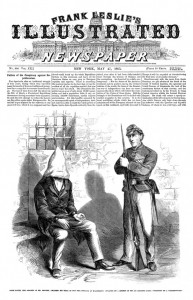

The Conspirator’s presentation of the usual historical drama cleanliness in its production and costume design also has been remarked upon by others, but I was taken aback by the related decision to shun using any actual contemporary visual and print media in the requisite flaring newspaper headlines that pepper the transitions in the film. The newspapers and magazines in 1865 certainly offer visually dramatic, if also distinctly historical, material that the camera can exploit to dramatic effect—yet, in The Conspirator, faux documents flash before our eyes featuring huge newspaper headlines accompanied by large tonal illustrations, neither characteristic of print journalism until late in the century. Moreover, for some reason the headline typography is consistently presented as under-inked—I assume because the production designer decided that this treatment would satisfy the audience’s expectation of an “old tyme” look.

I’m sure some will view my grousing as particularly trivial, and The Conspirator is definitely not alone among film historical dramas in preferring its own invented stand-ins for the visual culture in the past (one of my favorites being the 1860s Gustave Doré wood-engraved illustrated bible that the African captives read in Steven Spielberg’s 1997 film about the 1839 Amistad mutiny and subsequent trial). But, much like its willfully blinkered script, from which slavery is completely excluded (as well as the Surratts’ former ownership of slaves), The Conspirator chose to substitute its own imaginary notion of what constituted American print and visual culture over what Americans viewed and read—and, thus, how they understood the world around them—during and after the Civil War.

Last 5 posts by Josh Brown

- The Civil War Draft Riots at 150 – A Public Event - June 17th, 2013

- Alfred F. Young - November 7th, 2012