Visions of the City—Lost and Found

It’s a rare experience: that pleasant shiver of discovery as your eye settles on an image, a display, a scene that is so evocative (even if you don’t know of what) that you know it will leave an impression for a long, long time (like the glimpse of a young woman on the ferry recalled decades later by the octogenarian Bernstein in Citizen Kane: “I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.”). I know it might sound hyperbolic—if not hysterical—but, really, no kidding, it’s very close to the sensation I felt earlier this year when the cartoonist James Sturm showed me original sketches by the newspaper artist Denys Wortman.

It’s a rare experience: that pleasant shiver of discovery as your eye settles on an image, a display, a scene that is so evocative (even if you don’t know of what) that you know it will leave an impression for a long, long time (like the glimpse of a young woman on the ferry recalled decades later by the octogenarian Bernstein in Citizen Kane: “I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.”). I know it might sound hyperbolic—if not hysterical—but, really, no kidding, it’s very close to the sensation I felt earlier this year when the cartoonist James Sturm showed me original sketches by the newspaper artist Denys Wortman.

If the name Denys Wortman does not, itself, evoke some sort of image in your mind, that’s not a failing on your part. From 1924 to 1954, Wortman published six elaborate captioned drawings a week under the title “Metropolitan Movies” in the New York World—which, as the city’s daily newspapers collapsed from the mid-twenties onward, then became the World-Telegram in 1931, and in 1950 the World-Telegram and Sun. A student of Robert Henri, it is no exaggeration to say that each Wortman cartoon was an echo, refulgent of a later era, of the (retrospectively labeled) Ashcan artists: richly-observed vignettes of workplaces, homes, streets, and places of leisure that affectionately captured in numerous narratives (accented by captions written largely by his wife) and a strong sense of gesture, dress, space, place, and social class, everyday life in New York. (See the 1929 profile “All N.Y. Poses For Wortman’s Cartoons” on Allan Holtz’s always valuable Stripper’s Guide website.) Yet, after thirty years and thousands of cartoons, Wortman and his work were pretty much forgotten and rarely mentioned even in histories of newspaper cartooning.

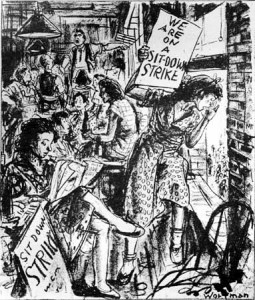

My shiver-of-discovery reaction on seeing Wortman’s actual sketches certainly stemmed from his masterly technique, the incredibly varied and often startling perspectives, and the layering of a multitude of stories in his compositions—and also because they sparked my own very early childhood memories of the remnants of 1930s and 40s New York City, especially in Chelsea and on the Lower Eastside. There was another sensation, though: weirder because I realized I had actually encountered Wortman’s art some twenty years earlier. I was in Providence, Rhode Island, doing research for the first edition of the American Social History Project’s Who Built America?, when I came across a very yellow clipping of one of his cartoons among the archival riches collected by labor historian Scott Molloy (comprising some 9,500 items now in the hands of the Smithsonian Institution). The drawing perched on the upper left corner of this blog posting is a pretty fair approximation of the lousy quality of the reproduction I saw published in the New York World-Telegram on March 25, 1937. But the crude picture of the young sit-down striker crying, “Mama. We’re makin’ history” nevertheless captured, better than any single photograph, the spirit and significance of that wave of activism (not to mention placing women in the center of a largely male-dominated story, Lorraine Gray’s wonderful documentary With Babies and Banners, on the Flint, Michigan, General Motors Sit-down strike, to the contrary notwithstanding). The cartoon appeared in, and has continued to appear in subsequent editions of, Who Built America?, not to mention the second CD-ROM based on the book and on our History Matters website. And over that time I assumed that Denys Wortman was an undeservedly forgotten woman cartoonist (Denys in the kingdom of my head pronounced Den-eese!).

Gender issues aside, only upon seeing Wortman’s much larger drawings did I also realize how poor were the reproductions that appeared in the newspaper: reduced in scale, rather than hiding imperfections, the rich detail was lost, and the crude reproduction techniques smothered Wortman’s subtle shifts in grays and white highlights, and obscured his wondrous handling of line and amazing ability to capture light and illumination.

Which is why I urge those of you near, or planning to be near, the island of Manhattan to make it a priority to go see “Denys Wortman Rediscovered,” the beautifully mounted exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York (at 1220 Fifth Avenue, between 103rd and 104th Streets) that will be open to the public until March 20, 2011. While nothing can quite capture the direct experience of seeing Wortman’s original drawings, the newly-published compendium of his work compiled by James Sturm and Brandon Elston, Denys Wortman’s New York: Portrait of the City in the 1930s and 1940s (with a terrific contextual introduction by Robert Snyder), does an excellent job of showcasing his work, with the reproductions of a sufficient size to allow you the singular thrill of perusing their wondrous details.

Finally, I realize I haven’t devoted space here to the heroic efforts that were involved in getting Denys Wortman’s life and work properly back in the public eye. For that story, and the thanks we owe in particular to James Sturm (and his Center for Cartoon Studies) and Denys Wortman VIII (whose website provides a wealth of material on his father), I urge you to take a look at the recent article in the New York Times by Carol Kino.

Last 5 posts by Josh Brown

- The Civil War Draft Riots at 150 – A Public Event - June 17th, 2013

- Alfred F. Young - November 7th, 2012