Two-Fisted Emancipator II

I know, I know: you’ve probably heard enough about Lincoln for now; indeed, you probably wouldn’t mind hearing nothing more about him until . . . well, at least until his quasquicentennial or even sesquicentennial celebration. But some of us, believe it or not, haven’t yet had our fill. Call me a masochist, but I remain intrigued about popular interpretations of the man and especially of iconic events such as his November 19, 1863 Gettysburg Address. Having already waxed unrhapsodic about Marvel’s anemic, six-page attempt to impress its readers about the man and the event by presenting him in close proximity to one of its trademark superheroes (albeit with the latter placed in the oddly passive role of spectator), it was with a mixture of curiosity and dread that I came across a new, more extended graphic treatment of the event.

I know, I know: you’ve probably heard enough about Lincoln for now; indeed, you probably wouldn’t mind hearing nothing more about him until . . . well, at least until his quasquicentennial or even sesquicentennial celebration. But some of us, believe it or not, haven’t yet had our fill. Call me a masochist, but I remain intrigued about popular interpretations of the man and especially of iconic events such as his November 19, 1863 Gettysburg Address. Having already waxed unrhapsodic about Marvel’s anemic, six-page attempt to impress its readers about the man and the event by presenting him in close proximity to one of its trademark superheroes (albeit with the latter placed in the oddly passive role of spectator), it was with a mixture of curiosity and dread that I came across a new, more extended graphic treatment of the event.

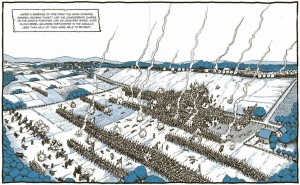

The back cover of C. M. Butzer’s recently published Gettysburg: The Graphic Novel indicates that it is for “Ages 9-14.” There are tell-tale signs indicating the book’s target market—the squat 7 x 9-inch format; the semblance of duotone in its color palette; the studious “Author’s Notes,” bibliography, and “webliography” in the back; and, perhaps most explicitly, the large, unproportioned heads of its characters—but I’m not clear why HarperCollins decided that the eighty-page book should be directed to children. There’s a certain (I’m not sure how to characterize it:) primerlike quality to Butzer’s drawing, but that’s offset by panoramic panels (above) and enough gore to satisfy adolescent male readers. That said, the severed limbs and terrible wounds are not offered as gratuitous thrills or for shock value but as part of the history of the war and, in one particular sequence, of battlefield medicine.

Butzer’s Gettysburg encompasses an impressive range of experiences and perspectives, including soldiers, freedpeople, local residents, doctors, and photographers. These vignettes are at times elliptical in the history conveyed and many end up relying on the author’s end notes to fill in the gaps—perhaps not the most satisfying way to supply information in a graphic narrative. Overall, though, Gettysburg does a very good job of introducing the battle and its aftermath, and it’s particularly good in telling a coherent story while suggesting greater complexity and that there’s much more for the reader to learn.

The one glaring problem in Gettysburg is Lincoln’s speech. I can’t figure out why popular histories, text or graphic, are so reluctant to wrestle with the Gettysburg Address. Or is it that, mistakenly, these accounts operate under the assumption that the speech’s significance and meaning are readily apparent? Offhand, I can’t suggest a smart visual approach to parsing the speech or helping readers understand its meaning beyond its eloquence. It might take an additional eighty pages to do it right—but I must admit that’s something I’d like to see.

Last 5 posts by Josh Brown

- The Civil War Draft Riots at 150 – A Public Event - June 17th, 2013

- Alfred F. Young - November 7th, 2012